Binairo, which is sometimes also called Takuzu, is a pure logic puzzle played on a variable sized grid. Using just 1s and 0s, it might be quick to learn but it can be a real challenge to solve!

In a hurry? Jump to: Rules / Tips / Worked Example / Video Tutorial / Download Free Puzzles / Books

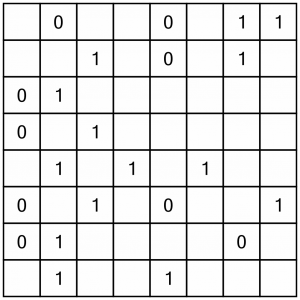

Here’s a small example puzzle:

The goal is to fill the grid with 1s and 0s, following certain rules.

There are only three rules to remember:

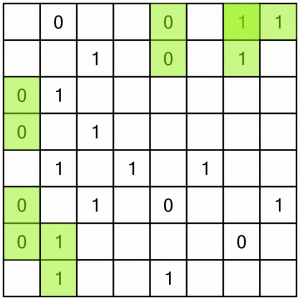

Here is what the example puzzle looks like once completed:

Every puzzle has a single valid solution, though of course there may be lots of ways to reach that solution.

Unlike many kinds of logic puzzle, Binairo is not necessarily easier to solve from the outside in; even the corners aren’t helpful. On the contrary, the easiest wins come from clusters of numbers.

Here are some tips on how to approach solving a puzzle. Below, we will work through an example from beginning to end.

As with all puzzles, there’s not a single correct way to solve a Binairo. The example presented here is just one way, and is a demonstration of the general techniques used.

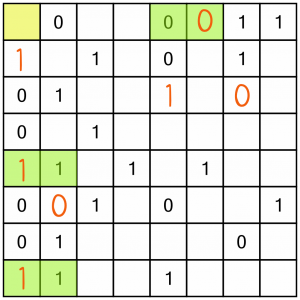

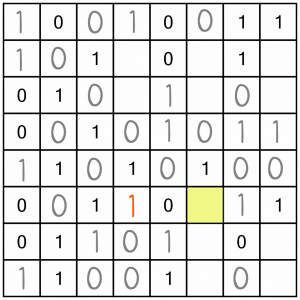

Here is the grid we are going to work through. This is a level 2 puzzle, so though it’s easy to complete, it still presents enough of a challenge to give an overview of the techniques used to solve these puzzles.

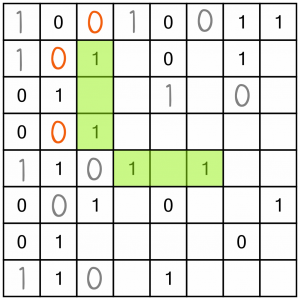

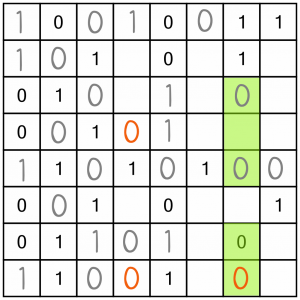

We’ll begin by looking for all the easy wins. Remember there are three kinds of easy win. First up, doubles (two adjacent numbers the same).

There are six doubles. We know that the numbers either side of them must be the opposite of the numbers forming the doubles, otherwise we’d be trying to put three numbers in a row, which isn’t allowed. So between them, these doubles allow us to solve seven cells. We’ll put those numbers in now.

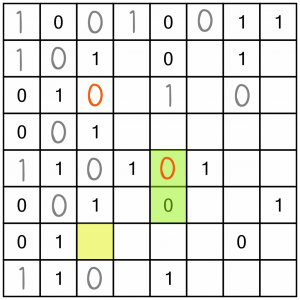

Filling those in gave us three new doubles. We’ve also got an almost completed column (another easy win). We can fill in the yellow cell straight away; we know we must have an even number of 0s and 1s in each row and column. That column already has four 0s, but only three 1s. Therefore the yellow cell must be a 1.

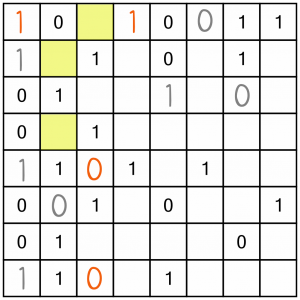

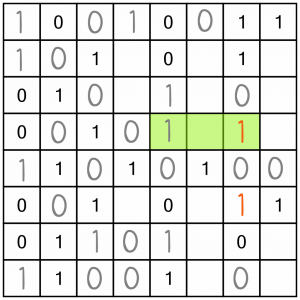

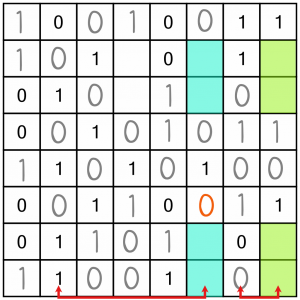

Now the top row is almost complete, so we can figure out what the one remaining (yellow) cell must be. We’ve got all the 1s, so it must be a 0.

We can also work out the two remaining cells in the second column must both be 0s, for the same reason.

We’ve used up all the easy doubles for now, so let’s check on another kind of easy win - empty cells with the same number either side. There are two such opportunities available here, so we can fill out those cells.

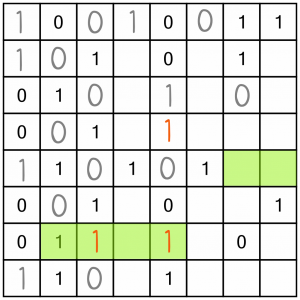

That’s opened up two new opportunities: there’s a single remaining cell in column three (yellow), and a new double in column five (green). Even without the double, we could complete that column just based on the count of 0s and 1s.

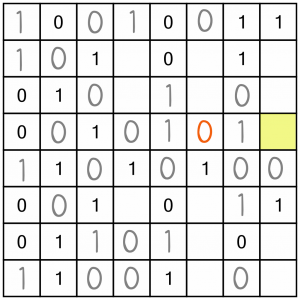

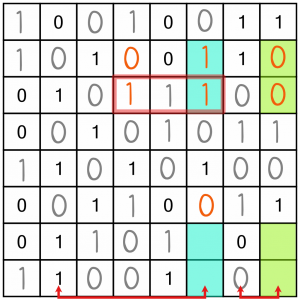

The penultimate row has a new double (which is also a single cell surrounded by two numbers the same).

Row five has a full complement of 1s, so we know the last two cells must both be 0.

We’ve got one more easy win for now (the green highlight). There are a couple more cells we can solve here too.

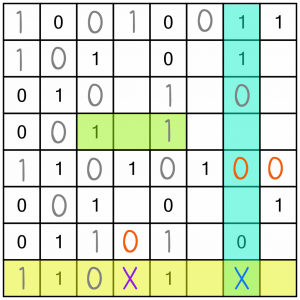

First, the blue column. It’s already got three 0s, and as this is an 8x8 grid we know we need one more. Although there are three empty cells, there’s only one into which we can place the missing 0 – the bottom cell marked with the blue X. If we put it in either of the others, we’d be making a row of three.

Next, the yellow row. We know that one needs three more zeros. We can’t put all of them in the last three cells, so one of them must go in the cell with the purple X.

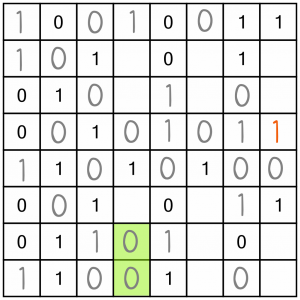

Now we’ve got a double and a single cell, although we don’t need them anyway because as there are four 0s already, both remaining cells in that column must be 1s.

Here’s another single we can fill in.

That gives us a row with one empty cell.

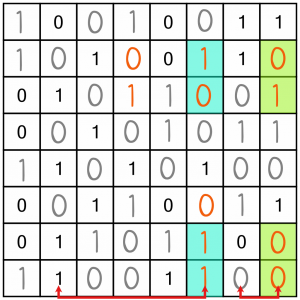

Here’s an easy double.

That gives us an almost complete row.

We’re out of doubles, and empty singles. In fact, we’re left with several pairs of cells and no obvious answers as to which way around to fill them.

But we do have a way to move forward. We can use several pieces of logic to solve the blue and green cells. We can combine our knowledge of what numbers we still need to place, along with the fact that no two columns can be the same. The column with the blue cells is shaping up to look a lot like column two. And the column with the green cells is looking like its neighbour to the left so far. These facts limit our placement options.

Let’s consider, for example, the end column. We must place three 0s somewhere. If we put them both in the top two free cells, that would make the two blue cells at the top of column six both 1s. But that would make it impossible to fill in the remaining free cells in rows two and three correctly:

This is wrong! Clearly that cannot be the solution...

In fact, if we work through the options, there’s only one way we can fill in the blue and green cells in such a way that the columns don’t duplicate others, and that allows us to complete the last two cells correctly. And that’s it – we’ve completed the puzzle.

Ready to have a go yourself? We’ve put together a taster of four puzzles for you, including the example above. You can download and print the PDF below. Solutions are included, but no cheating!

Finished the taster and want more Binairo in your life? No problem! Get 120 carefully crafted puzzles set over seven levels in Puzzle Weekly Presents: Binairo – it's great value!

We publish Binairo puzzles in Puzzle Weekly from time to time. Puzzle Weekly is our free weekly puzzle magazine – find out more, and get your copy, here